Peer Review Article on Health Education and Obesity in Schools

- Review

- Open up Admission

- Published:

A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions with health pedagogy to reduce body mass index in adolescents aged 10 to 19 years

International Periodical of Behavioral Nutrition and Concrete Activity volume 18, Article number:i (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Adolescents are increasingly susceptible to obesity, and thus at risk of later not-infectious disease, due to changes in food choices, physical activity levels and exposure to an obesogenic environment. This review aimed to synthesize the literature investigating the effectiveness of wellness education interventions delivered in school settings to prevent overweight and obesity and/ or reduce BMI in adolescents, and to explore the key features of effectiveness.

Methods

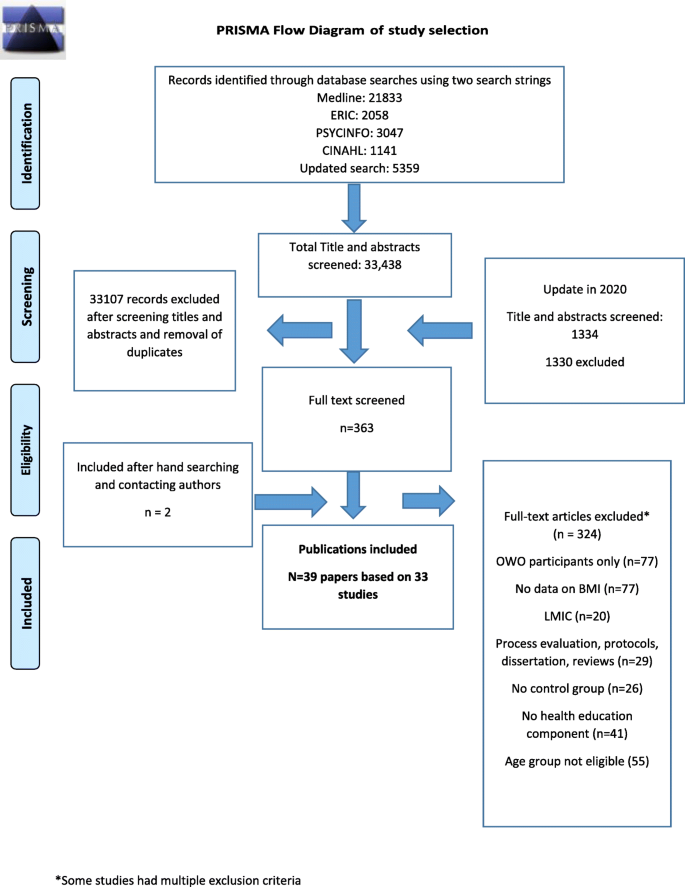

A systematic search of electronic databases including MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsychINFO and ERIC for papers published from January 2006 was carried out in 2020, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies that evaluated health didactics interventions in 10–xix-year-olds delivered in schools in high-income countries, with a command grouping and reported BMI/BMI z-score were selected. Three researchers screened titles and abstracts, conducted data extraction and assessed quality of the total text publications. A 3rd of the papers from each set up were cross-checked by another reviewer. A meta-analysis of a sub-set up of studies was conducted for BMI z-score.

Results

Thirty-three interventions based on 39 publications were included in the review. About studies evaluated multi-component interventions using health education to improve behaviours related to diet, physical activity and body composition measures. 14 interventions were associated with reduced BMI/BMI z-score. Most interventions (northward = 22) were delivered by teachers in classroom settings, 19 of which trained teachers before the intervention. The multi-component interventions (north = 26) included strategies such every bit environs modifications (due north = 10), digital interventions (n = xv) and parent involvement (n = sixteen). Fourteen studies had a depression risk of bias, followed by 10 with medium and nine with a high gamble of bias. Fourteen studies were included in a random-effects meta-analysis for BMI z-score. The pooled approximate of this meta-analysis showed a pocket-size departure betwixt intervention and control in change in BMI z-score (− 0.06 [95% CI -0.10, − 0.03]). A funnel plot indicated that some degree of publication bias was operating, and hence the upshot size might be inflated.

Conclusions

Findings from our review suggest that school-based health education interventions take the public health potential to lower BMI towards a healthier range in adolescents. Multi-component interventions involving key stakeholders such equally teachers and parents and digital components are a promising strategy.

Background

Approximately 340 million children and adolescents aged five–19 years had overweight or obesity globally in 2016 [1]. Almost 80% of adolescents with obesity volition accept obesity equally adults [2] and the prevalence of morbid obesity in adults is college amidst those who had obesity as adolescents [iii]. Obesity in childhood and boyhood is associated with an increased take a chance of non-catching diseases (NCDs) such as Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive lung disease and some forms of cancer [four]. Adolescents with excess weight or obesity often take decreased self-esteem and may be subjected to bullying and bigotry, increasing the gamble of poor psychological wellness and eating disorders [5, 6].

Boyhood is a transitional period characterized past critical changes in torso composition, insulin sensitivity, wellness behaviours and psychological and social functioning, also every bit increased autonomy [v, 7]. The likelihood of unhealthy eating behaviours, loftier screen-time, matted slumber patterns and decreased participation in physical activity (especially among girls) increases during adolescence [8,ix,10,11]. Factors leading to adolescent obesity tin can be broadly categorized into private (food preferences, taste and perceptions, self-efficacy for making healthy choices, and convenience), social (including family unit and peer relationships), demographic (socioeconomic condition (SES)) and environmental (mass media, easy access to fast-food outlets and vending machines, lack of safe active recreation and travel options) factors [12, thirteen]. It has been suggested that obesity prevention interventions may exist more effective in adolescents than younger children, equally they are more likely to sympathize the concepts and have more autonomy, for example near food choices [xiv].

Previous systematic reviews roofing the menstruum before 2006 have evaluated the effectiveness of interventions to improve obesity-related outcomes such equally body mass index (BMI), concrete activity and dietary behaviours in children and adolescents together, or for detail countries [15,xvi,17,18]. All the same growing evidence suggests that the school setting provides a platform for effective and sustained intervention delivery to prevent overweight and obesity [xix, 20]. Such interventions have often incorporated methods such as wellness education, providing salubrious school meals, parental involvement, and community date [15, 21,22,23]. As adolescents are already engaging in formal education and activities with their peers, schools provide an ideal platform for delivering health interventions, just nigh reviews examining the effects of schoolhouse-based programmes on BMI have considered children and adolescents together. A meta-analysis (n = 5) showed no significant change in the BMI of children and adolescents receiving the intervention compared with command groups but data disaggregated for two–19 year-olds were non presented [sixteen]. Fewer trials based in schools were specifically for adolescents, [22] but irresolute health behaviour patterns may hateful that strategies to prevent obesity in this age group crave a unlike approach from those used in younger children.

In the Great britain, increasing health education in schools has been recommended as role of the regime's Childhood Obesity Strategy [24]. Health educational activity, provided in daytime and after-school programmes, has been widely recommended every bit a tool to address obesity [25], by encouraging behaviour change and improved wellness literacy [26]. However, to date, reported effects of health didactics on body limerick and weight accept been mixed, possibly due to the brusk duration of interventions and a lack of attention to accompanying lifestyle changes exterior the school environment [27]. The effectiveness of health education as a mode of reducing BMI in boyhood has not been reviewed.

Aim

The aim of this review was to synthesize prove to answer the following questions: 1) What is the effectiveness of wellness education interventions delivered in schoolhouse settings to forestall overweight and obesity and/ or reduce BMI in adolescents? two) What are the fundamental features of effective interventions?

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive and systematic search of published literature was undertaken in Jan 2017, and updated in June 2020, in accord with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [28] and the Academy of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Guidelines [29]. Nosotros focused our searches on the catamenia since 2006 which was non covered by existing high-quality systematic reviews of school-based interventions. The following electronic databases were searched in total: MEDLINE, ERIC, PsychINFO and CINAHL. A combination of medical subject area headings (MESH) and costless text keywords were used to notice intervention studies, limited to English linguistic communication and published between Jan 2006 and 2020. Carve up search strings were developed for diet (eastward.g., fruit), physical activity (e.g., exercise, sport) and obesity (e.g., overweight, obese), intervention (e.k., education, wellness literacy) and adolescents (e.yard., teen, youth) (meet Supplementary Material one). We consulted an information specialist (LP) to review and comment on the search strategy and contacted experts in the field to identify studies not located in the database searches. Reference lists of included articles were besides screened. The proposal for this review was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42016053477).

Selection criteria

Experimental studies that investigated the effectiveness of health education interventions in adolescents aged ten–19 years in schoolhouse settings [30], and which reported BMI and/or BMI z-scores as outcomes [31] were included in this review. Tabular array i presents further details on the rationale for the inclusion criteria. Included studies needed to have a control or comparison group and pre/post-intervention measures for BMI outcomes (at to the lowest degree ane post-intervention measure out). BMI and BMI z-score were selected as they are commonly used for assessing overweight and obesity in adolescents. Differences in education systems, modes of commitment of interventions, cultural and contextual differences could touch the relevance and applicability of the findings. Therefore, just studies from loftier-income countries were included in this review. The definitions for income groups for countries by World Bank (2020) [32] were used to exclude low-and eye-income countries (LMICs). Nosotros also included multi-component intervention studies that addressed other issues such as unhealthy diet and physical inactivity if they too reported BMI outcomes. Health education was divers as 'whatever combination of learning experiences designed to facilitate voluntary adaptations of behaviour conducive to health' [33]. Past this definition, interventions delivered in an educational setting, which provided information on improving diet and/or physical activity and preventing excess weight gain were included. Educational interventions supplemented by behaviour change techniques and using innovative tools for dissemination such equally digital interventions were also included. As schools often accept general wellness instruction equally part of their curriculum, just interventions that were delivered every bit an addition to existing lessons, with the main component delivered inside the school environment, were included. Studies focusing only on specific groups (e.g. adolescents with obesity, or specific medical conditions) were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Titles and abstracts were downloaded, and duplicates were removed using EndNote bibliographic software. Iii authors (CMJ, PHJ and MB) screened titles and abstracts that met the inclusion criteria. Full texts were then assessed for eligibility past iii reviewers (CMJ, PHJ, MB) and any disagreements resolved through give-and-take with a fourth reviewer (JB). Data were extracted from included studies using a form to capture cardinal data on populations, intervention strategies and results. A modified version of a quality assessment rubric, based on CRD guidance, was used to assess run a risk of bias in included studies in relation to the review questions. Take a chance of bias scores ranged from − half dozen to + 11 and were categorized into depression take chances (+ 5 and above), medium hazard (+ one to + iv) and high run a risk (0 to − vi). Scores of + 1/ 0/ -one were given for dissimilar criteria (e.g. selection criteria, analytical methods) and tallied to provide a last score for adventure of bias. For example, studies were awarded + ane for randomized controlled trials, 0 for quasi-experimental studies that include a control group, and − 1 for experimental studies that do not utilise a control group. A full description of the assessment criteria can be institute in the supplementary textile. The included studies were divided into two sets, and reviewers (CMJ and PHJ) reviewed i set each. Papers identified through an updated search (2018–2020) were reviewed by iii reviewers (PHJ, CMJ and MB). To ensure consistency, a third of the papers from each set were cantankerous-checked past another reviewer.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted for studies presenting information on BMI z-score. Although some bug were present due to heterogeneity of target groups, specific intervention components and how outcome measures were presented, sufficient data were available for meta-assay in 14 of the 33 included studies [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Studies not included in the meta-analysis did not provide results for BMI z-score simply reported a change in BMI, BMI percentile or prevalence of obesity/ overweight based on calculated BMI or BMI z-score. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran's Q and the pct of variability due to heterogeneity was quantified using I2. To account for the heterogeneity between studies, a random-effects model was used in the meta-analysis. Where follow-up results were recorded at different time points during data extraction, the longest follow-upwardly measure out was used, and, where available, sub-group results (based on gender) were obtained. Meta-analysis was conducted on the full dataset from the 14 studies and then repeated according to gender for those studies that reported such findings separately. Due to the limited number of studies eligible for meta-analysis, subset analyses by intervention features, risk of bias and fashion of delivery could non be conducted. Funnel plots were created to assess the possibility of publication bias for studies included in the meta-analysis (northward = 14). All analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, United states of america).

Results

Results of literature search

The total search retrieved 34,772 records. Post-obit removal of duplicates, 32,828 were screened past title and abstract. The remaining 363 full text articles were screened, of which 39 publications met the inclusion criteria (run into Fig. one PRISMA flow chart). Some of the publications were based on the same written report cohorts just reported different outcomes of the same intervention. Where this occurred, nosotros grouped the publications by study cohort for reporting and analysis.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of study pick

Characteristics of included studies

We identified 39 papers, based on 33 studies [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Half-dozen studies recruited boyish girls only [36, xl, 44, 47, 61, 63] ane boyish boys only [42] and i study included parent-student dyads [66]. Nearly of the studies (n = 27) focused on adolescents aged x–14 years [34, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 44,45,46,47,48, 50, 52, 54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], and six recruited participants from high schools/secondary schools without defining an age range [35, 43, 49, 51, 53, 55]. Eighteen reported the use of behaviour change theory to inform the development of their interventions [36, 38, forty,41,42, 44, 47, 52,53,54,55,56,57, 61, 63,64,65,66] with the most common theory being social cerebral theory [36, 38, 41, 42, 52, 53, 55, 56, 61].

Most studies evaluated multi-component interventions which, in addition to wellness teaching delivered in the classroom, included components such every bit homework activities, environment modification, physical activity classes, and fruit and vegetable breaks during form (northward = 26). The remaining seven interventions included health didactics interventions merely [34, 45, 50, lx, 62, 64, 65]. Tabular array 2 provides an overview of the features of included studies and percentage of effectiveness for each component.

Thirteen of the studies included had an later-school component such every bit monitoring nutrition and physical activeness habits at home, providing additional resource to support behaviour change at home (e.one thousand., recipe cards), community activities and social events [35, 36, 38, 40, 43, 46,47,48, 55, 57, 59, 63, 65, 66]. Twelve studies provided additional sessions for organised sports or clubs to increase practise or physical activeness [36, 42,43,44, 47, 51–53, 56, 58, 63, 64]. Table 3 describes the characteristics of each intervention. Quality cess scores are reported in Tabular array 4. A quality cess of the 33 studies included in this review indicated that xiv had a depression hazard of bias compared with ten with medium and 9 with a high gamble of bias. Risk of Bias scores ranged from − 3 [49, 61] to + 11 [47]. Equally nigh studies were multi-component, developing a narrative summary with exclusive groups based on characteristics was not viable. For word, we nowadays groups based on their dominant intervention components.

Mode of intervention commitment

Near interventions were delivered by teachers (n = 22) [34,35,36,37,38,39,twoscore,41,42, 45, 46, 48,49,50, 52,53,54, 57, 59, 61, 62] followed by researchers [35, 55, 56, 58, 60, 63,64,65], school nurses [44, 47] and in others a schoolhouse project officer and concrete teaching teacher [43] or projection managers [66]. The study by Bogart et al. trained 'peer leaders', in add-on to teachers, to promote and model healthy behaviours and appoint other students [48, 70]. 19 studies reported training the teachers to deliver the intervention through a variety of means including workbooks or other training materials and face-to-face sessions [34, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43, 45, 48,49,50, 52,53,54, 57, 59, 61]. For instance, the Health in Adolescents (HEIA) Intervention [xl] included two courses in physical education based on a previously validated program for teachers [71]. Millar et al. provided continuing professional person development (CPD) programmes for physical education teachers [43]. CPD was defined equally the skills, cognition and experience gained by teachers beyond whatever initial formal or breezy training.

Parental involvement

Xvi interventions had parental involvement [36, 37, 39, twoscore, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49, 52,53,54,55,56, 63, 66]. The modes of parental involvement are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Busch et al. conducted an educational intervention integrated into the regular curriculum [49]. The study by Mihas et al. aimed to improve cognition, behavioural adequacy, expectations and self-efficacy [54]. Parents were also encouraged to improve their own dietary behaviours. Grydeland et al. collaborated with schoolhouse principals, teachers, school health services and parent committees [40]. Teachers delivered the lessons and handed out monthly factsheets to parents and an activity box to students with sports equipment and toys to promote physical activity. Parents in the report conducted past Bogart et al., besides engaged in homework activities with the students, which included completing worksheets on nutrient preferences amid different members of the family and types of fruits and vegetables kept at home [48]. Finally, iii of the studies only provided data to parents [37, 43, 53]. Parental interest was a key component of the Guys/ Girls Opt for Activities for Life (GOAL) intervention [66] which included parent-adolescent dyads for group meetings targeting self-efficacy, social support and motivation. The meetings aimed to assist parents in supporting students' physical activity and healthy eating habits through word on behavioural strategies as well as salubrious cooking sessions.

Digital interventions

Xvi studies used digital media such as apps, websites, CD-ROMs and figurer-tailored information [35,36,37,38, 40, 42, 43, 46, 50, 55, 59, 63,64,65,66]. The HEIA intervention included the provision of information to increase awareness of recommended physical activity levels and fruit and vegetable consumption [40]. They as well provided tailored communication to students (a subgroup within the intervention) on how to change dietary habits, screen time and physical activeness levels. An intervention in Italian schools included sixteen health-promoting lessons (delivered by nutritionists) forth with text letters for daily practise and nutrition advice, as well equally environmental modification (e.g. vending machines for healthy nutrient items) [37]. This quasi-experimental study evaluated an intervention in which automated text letters were sent to students and parents three times a week, close to mealtimes, to promote discussions in the family related to healthy eating habits. The FATaintPHAT intervention consisted of a computer-tailored intervention to help foreclose excessive weight gain by improving diet, reducing sedentary behaviours and increasing concrete activity, with additional modules on weight management [50]. The modules also included specific goal-setting and action planning with normative and comparative (with peers) feedback. Three studies also used social media (such as Facebook) to provide a platform for communication with the researcher (who delivered the intervention) [64], data on sessions [64], and weekly Facebook participation for parents in the GOAL programme [66]. Another intervention [65] used a social-network based eHealth intervention to improve nutrition and physical activeness habits. The participants could use the social network platform to develop friendships and interact with each other while receiving information about nutrition and physical activity. They were besides given rewards for improving their habits.

Change in environment

X studies included measures to ameliorate the environment, in improver to educational components, or schoolhouse policy change to increase accessibility and/or ameliorate facilities in schools for sports, social marketing and providing healthier meals [37, 39,40,41, 43, 49, 52, 53, 58, seventy]. Three studies also applied environmental modification in neighborhoods through community activities or providing data on improving home/neighborhood environment [35, 49, 59].

Millar et al. provided a school-based intervention with a community component focusing on promoting healthy breakfasts, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption, and improving school meals [43]. Rosenbaum et al. delivered an intervention with the principal aim of reducing risk of Blazon 2 diabetes in adolescents consisting of health, diet and exercise classes, a programme on diabetes risk along with 45-min sessions on Blazon 2 diabetes prevention in class [58]. The Match intervention [41] and the COPE plan [53] also used additional physical activity sessions to support the educational interventions. COPE was a manualized 15-session educational and cognitive behavioural skills edifice programme that also aimed to forestall symptoms of low in adolescents. The Eat project included school environmental changes such as providing healthier snacks in vending machines, placing educational posters throughout the school, and creating additional play areas [37]. Bogart et al. also used additional nutrient surround modification strategies past providing a variety of fruits and vegetables during school tiffin and free h2o [48]. Campaigns were as well conducted to disseminate the messages widely through the schools. Two studies included lunch sessions or breaks to provide healthy foods such as fruit and vegetables [40, 55], and 2 trialed a modified school nutrition policy [39, 49].

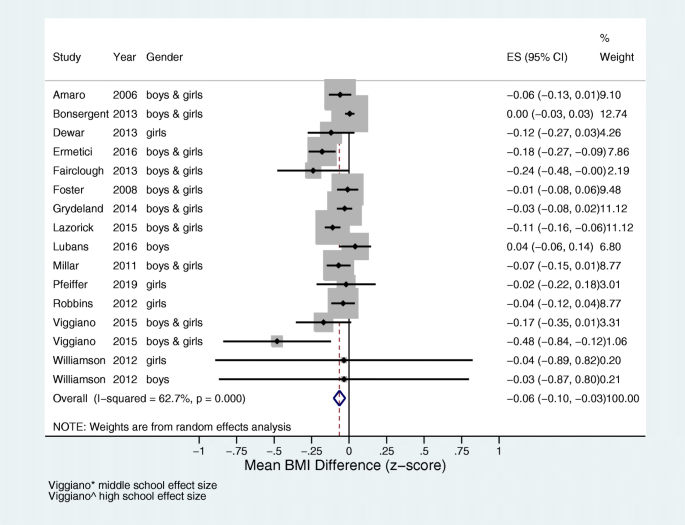

Meta-analysis

Of the 33 studies included in the review, 14 studies reporting outcomes based on BMI z-score were included in the meta-analysis [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. There were besides few studies that reported event sizes in a consequent mode to conduct further meta-analyses. In that location was a high level of heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 62.7%), as seen in Fig. 2. The overall pooled estimate of alter in BMI z-score in the intervention group, compared with the control group, was − 0.06, 95% CI (− 0.10, − 0.03); p < 0.001.

Meta-analysis of 14 studies showing the effect of educational interventions on BMI z-score. The pooled estimate shows significant deviation between intervention and control in change in BMI z-score

We constructed a funnel plot using the mean departure and standard error of the mean departure in BMI to assess the gamble of publication bias (Fig. 3). The asymmetry in the plot indicates a degree of bias within this subset of xiv studies included in the meta-analysis, which might take led to overestimation of result size. The findings discussed in the meta-analysis and narrative synthesis should therefore be interpreted with circumspection due to the likelihood of publication bias, high heterogeneity and small upshot size.

Funnel plot for gamble of publication bias

Cardinal features of studies with significant effect on BMI outcomes

Overall, 14 studies reported a significant reduction in BMI and/or BMI z-score [37,38,39,forty,41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 52–54, 58, 65]. Of these, 4 studies reported significant effects in only a subset of the population (See Table iii) [40, 48, 49, 65]. All effective studies with a significant effect on BMI outcomes had a face-to-face component for intervention delivery in the classroom, except i, which was only digital [65]. Of the sixteen studies that included parents, eight reported pregnant effects on BMI outcomes [37, 39, twoscore, 43, 49, 52,53,54]. Seven of the effective interventions were RCTs [38,39,40, 45, 48, 52,53,54] and seven were not-RCTs [37, 41, 43, 49, 58, 65]. One quasi-experimental report used a chapters-edifice approach with a customs-based component to promote healthy eating and physical activity [43]. There was high variation in the duration of the interventions, from 12 weeks [54] to 3 years [43], with four studies in which the intervention was delivered for a twelvemonth or more [37, 39, 43, 49]. Even though 14 studies showed pregnant result on BMI outcomes, only four studies had a low adventure of bias [45, 48, 52, 53]. Five studies had a high adventure [39, 43, 49, 58, 65], and the residue a medium chance [37, 38, twoscore, 41, 54], and this could affect the reliability of the findings. Some studies that were of a low risk of bias did not evidence pregnant effects of the intervention on BMI outcomes [36, 42, 44, 47].

Of the 22 interventions delivered by teachers, twelve showed significant effects on BMI outcomes [37,38,39,40,41, 43, 45, 48, 49, 52,53,54]. Providing CPD/training for teachers prior to the intervention, including some form of face-to-confront sessions such as workshops and seminars, was a feature of constructive interventions. In the Change! intervention, Fairclough et al. developed the curriculum and resources through formative work with teachers, parents and children [38]. This intervention focused on the interaction betwixt social and environmental factors and their effect on behaviour and provided education on concrete activity and nutrition. Subgroup analysis revealing that post-intervention (xx weeks) effects on BMI were significantly greater in girls, but effects on BMI were not sustained at thirty weeks. In the Kaledo study, teachers were trained in how to facilitate and supervise students while playing the game (Kaledo) and there were sustained meaning reductions in BMI z-score at six and 18-month post-intervention [45]. The game was personalized (participants entered their BMI values) and included a 'penalisation and reward system' for specific dietary behaviours. Information technology aimed to amend nutrition cognition and influence dietary habits and eating behaviours of adolescents. Three studies provided more intensive CPD for at least 1 day [39, 41, 53], with one study providing 10 one-60 minutes training sessions beyond the whole twelvemonth [39].

Five interventions based on the on social cognitive theory constitute a statistically significant upshot on BMI outcomes [38, 41, 52,53,54]. The Salubrious study was a multi-component study which included parents, environmental change, homework activities during breaks and interactive educational lessons in form called 'Wink' delivered by teachers [52]. The module targeted sensation, knowledge, behavioural skills such as goal-setting and peer influence. However, the intervention was delivered in a schoolhouse with high proportion of ethnic minorities who were at a chance of diabetes (54.2% Hispanic, eighteen% black). The study led to a not-pregnant decrease in prevalence of overweight and obesity in both intervention and control schools. Additionally, the mean BMI z-score was significantly lower in the intervention schools than in the command school. The result of the intervention was higher amidst students with obesity. However, 2 multi-component interventions with depression risk of bias (NEAT girls and ATLAS) were also based on social cognitive theory and had no short or long-term effects on BMI. These interventions included sports sessions, seminars and nutrition workshops, parent newsletters, pedometers and text letters [36, 42]. Too, of the 16 interventions that included parental involvement, 8 plant meaning outcomes on BMI [37, 39, 40, 43, 48, 52,53,54]. The mode of parental involvement in the effective interventions included parent newsletters [52, 53] homework with parents [48], text messages [37], nutrition education and behaviour change for parents [40, 43, 54]. A quasi experimental written report [65] led to significant improvement in a subgroup with initial BMI age-adapted percentile > fifty%. Interestingly, there was too a significant increase in BMI age-adapted percentile for students with BMI percentile less than 50% at baseline. The intervention used methods such as developing peer networks and rewarding adept practices to encourage adolescents make healthier choices.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to synthesize evidence regarding the effectiveness of school-based health pedagogy programmes in reducing BMI and preventing overweight and obesity in adolescents. Overall, we found minor but significant reductions in BMI z-score. All but two [58, 65] of the constructive interventions were delivered by teachers who were trained prior to the intervention, suggesting that though school-based interventions are often delivered through schoolhouse-staff, appropriate grooming/ CPD prior to the intervention could exist a crucial component to back up the provision and uptake of the intervention. Similarly, many of the effective interventions had included parental involvement and modifications to the school surroundings. The studies in this review mainly evaluated multi-component interventions that used health education as a tool to improve health behaviours related to diet, physical activeness and body composition measures.

Schools are a commonly-used setting for behavioural interventions for preventing obesity and overweight and improving nutrition and physical activity levels in children and adolescents, as they provide an like shooting fish in a barrel aqueduct for accessing this age grouping. However, previous reviews of school-based interventions have shown mixed results for BMI outcomes [72, 73]. These reviews suggest that, for children and adolescents, effective interventions targeted direct concrete action and weight reduction through concrete education programmes combined with diet education. Some studies have shown improvements in the prevalence of overweight and obesity within this age group only only pocket-size effects on BMI [23, 74]. Dietz and Gortmaker (2001) developed a logic model for schools describing the range of factors that influence the energy balance in students [75]. These included a coordinated school health programme that promoted salubrious diets and physical activity, school policies and physical educational activity sessions in schools and the surrounding community, along with ecology factors. The results of the present review suggest that schools have the opportunity to finer deliver evidence-based interventions to forbid obesity.

Various creative methods have been used to engage adolescents in the studies in this review, such as lath games [45], digital components (online counselling, SMS messaging) [36, 37, forty, 55, 57, 59, 65, 66] and retreat days [55]. A contempo systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of digital interventions in improving nutrition quality and increasing physical activity in adolescents, suggesting that significant behaviour modify can exist achieved when health education, goal setting, self-monitoring and parental interest are included (mainly using web-based platforms, followed by text messages, and games) [76]. Computer-based nutrition pedagogy has likewise led to short-term improvement in BMI [77].

The success of interventions with wellness pedagogy also depends on how the messages are delivered [78]. Complex interventions that are more engaging for adolescents should be developed based on user preferences [79]. Recent RCTs such as the LifeLab intervention have focused on improving adolescents' understanding of the scientific discipline behind wellness messages and motivating them to improve their nutrition and physical activity levels through hands-on engagement with scientific discipline [lxxx]. This complex intervention likewise aims to better health literacy in adolescents, with preliminary results showing an improvement in their cognition almost risks of NCDs.

It must be noted that many of the studies included in this review were effective in improving other outcomes such as diet, physical activity levels and torso fat percentage [34, 37, 44,45,46, 51, 53, 57, 58]. For instance, three studies with no furnishings on BMI significantly improved levels of moderate to vigorous physical activeness [44, 51, 57], and another led to reduced body fatty per centum [46]. Four studies with no result on BMI recruited teenagers with low levels of activity [36, 44, 51, 56] or low cardiorespiratory fitness [56] at baseline, which could have affected the uptake of the intervention. Similarly, some interventions led to a significant effect on BMI for adolescents with obesity at baseline [48, 52, 53]. This could potentially be due to differences in physiological responses to weight loss interventions between adolescents with obesity and those with normal BMI [81]. Information technology should be noted as well that, although we have excluded studies focusing on adolescent eating disorders, future interventions should consider potential unintended effects on trunk image, eating disorders and other psychological attributes [82].

Office of stakeholders

Effective interventions oftentimes included key stakeholders such as teachers and parents. Previous studies related to other issues in adolescence such as consequences of booze consumption have shown that students preferred interventions delivered by teachers [83, 84] and thus the teacher-student relationship tin can support the effectiveness of school-based interventions. However, these findings should be interpreted with circumspection. It was not possible to perform a subgroups analysis to determine the role of key stakeholders in the included studies.

Previous systematic reviews in this area reached like conclusions; that constructive physical activity-based interventions, resulting in improved BMI outcomes, were characterized by familial interest and training for teachers and students on behavioural techniques such as self-monitoring [73]. In this review, most of the effective studies were facilitated by teachers who received CPD in a face-to-face format. Behaviour change frameworks have highlighted the importance of 'facilitators' (e.g. qualifications and feel of those delivering the intervention) and 'teaching' (pedagogy strategies used by facilitators to deliver the intervention components effectively) in improving intervention engagement and outcomes [85]. A systematic review of teacher CPD in school-based physical action interventions showed that such programmes were beneficial, particularly when they were conducted for more than 1 twenty-four hours, provided comprehensive pedagogy content, were framed by a theoretical model and measured teachers' satisfaction with training and content [19]. During data extraction, the reviewers noted that details of instructor CPD are often not elaborated upon or even reported in studies, and hence may have been missed by the present review. The 'Information technology's your move!' project, which used peer-led approaches and chapters-building for teachers, schools and parents highlighted certain challenges such as making time for additional CPD activities along with normal professional commitments for teachers [86]. The authors recommended developing strategies for improving leadership for such complex interventions. Other bug that hinder delivery through teachers in schools include a lack of fourth dimension or training and dubiety about their power and office. Many teachers believed that obesity is a status that requires treatment [87]. School teachers and personnel often receive little or no training in diet or obesity prevention techniques [xx, 88, 89]. Providing CPD for teachers for intervention delivery can help them to feel more confident and is part of adopting a health-promoting schools approach that encourages engaging parents and communities [20].

According to the wellness promoting schools framework of the International Union for Wellness Promotion and Pedagogy (IUHPE), schools have an essential role to play in health education for children and young people [ninety]. What is less clear is how best to engage with schools and provide evidence-based effective interventions. Our findings suggest that those interventions which showed improvement in BMI outcomes, worked with the school workforce to deliver the intervention. Hence, future interventions could benefit from planning with the education system, and from capitalizing on the expertise of teachers to best deliver messages and appoint young people with interventions.

Strengths and limitations

Other systematic reviews accept previously investigated the effectiveness of school-based obesity prevention in children and adolescents; even so, this newspaper is the get-go to synthesize evidence for BMI outcomes, exclusively in adolescents. Previous reviews explored a broader historic period range (children and adolescents), different settings (global), or types of interventions (e.thou. school and communities). While these reviews helped in providing an overview of the types and effectiveness of interventions for children and teenagers, our review provides in depth data on school-based interventions forth with specific recommendations for school stakeholders. The review followed standardized guidance for conducting systematic reviews (full PRISMA checklist in supplementary material) and a rigorous assessment of risk of bias past ii independent researchers and reported a detailed narrative synthesis of included studies. A random effects model was used for meta-analysis given the heterogeneous nature of the included studies. Only adjusted results were used for the meta-analysis to reduce bias. Due to the small number of studies eligible for the concluding meta-analysis, non-RCTs were also included to cover the evidence available. Nosotros constructed a funnel plot for the studies included within the meta-analysis. This suggested a caste of publication bias which might have led to over-interpretation of upshot size within the meta-analysis. The exclusion of studies that considered other anthropometric outcomes such every bit body fat percentage and waist circumference is an obvious limitation. Though these of import anthropometric outcomes predict future risk of NCDs, systematic reviews take shown that the use of BMI to define obesity in children and adolescents is highly specific, admitting with low to moderate sensitivity [91]. To overcome this issue, in the meta-assay we focused on BMI z-score over absolute BMI or modify in BMI, which practise non account for boyish age [92]. Finally, every bit unpublished analyses, briefing proceedings and greyness literature were not reviewed, there is a possibility that other schoolhouse-based interventions were disregarded. Finally, the generalisability of our findings may be express to high income settings. Although these findings are more than directly applicable to interventions developed in school-based settings, the insights volition be of utilise to shape interventions aimed at adolescents.

Recommendations and implications for enquiry and public health

A detailed assay of the content of the interventions and comparing based on components was not feasible, as studies frequently did not include adequate details on these factors in their papers. Time to come publications of RCTs should consider using standardized ways of reporting intervention details and results, for example using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide [93]. This improves completeness of reporting for individual study evaluations and further assists reviewers to collate and synthesize the findings. Similarly, time to come RCTs can consider including mediation analysis of behaviour change components in complex interventions.

Systematic reviews take oft been criticized for inadequate consideration of the contexts in which interventions are delivered [94]. Contextual and cultural factors, educational activity systems and prevalence of malnutrition can influence the delivery and uptake of interventions and their effectiveness. Hence, simply high-income countries were included in this review. This could have led to omission of recent interventions in LMICs using multi-component behaviour change theories and we recommend that research already conducted in LMICs needs to be reviewed, considering the co-beingness of other forms of malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies with babyhood overweight and obesity, to identify the best platforms for interventions in such countries [95]. Similarly, in high-income settings, childhood obesity is oft associated with lower SES and poor food environment [96]. While some studies in this review specifically targeted student/ schools from deprived areas [42, 47] hereafter studies demand to consider the barriers faced by students from schools in low-income areas who tend to have poorer diets and low physical activity levels use this data to develop targeted interventions. Policies for schoolhouse health should consider including wellness pedagogy for obesity prevention in personal social wellness education curriculum, for example, to support the wider public wellness strategies for obesity prevention. While our review shows that short-term outcomes for BMI can be modified through school-based interventions, further studies demand to assess the long-term effects of these interventions and consider the sustainability and implementation at a population level.

Conclusions

The findings of this systematic review have implications for research and policy in high-income countries, to ameliorate BMI outcomes in adolescence. Overall, our results suggest that school-based health education interventions could potentially help in improving BMI outcomes in the adolescent age group. Interventions should target the biological, psychosocial, environmental and behavioural influences on diet and physical action. As many of the face-to-face interventions were effective, policy-makers could consider supporting schools to find ways to enable such interventions. Near school-based interventions were delivered past teachers and, including a CPD plan could amend teachers' confidence in delivering interventions. Alongside schools, parents should be engaged past adopting multi-component strategies to prevent obesity and overweight in adolescents. The research customs should facilitate stronger working relationships with and between public wellness and didactics teams.

Availability of data and materials

N/A

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CPD:

-

Standing Professional Evolution

- CRD:

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination

- HEIA:

-

Health in Adolescents

- LMIC:

-

Low- and Centre-Income Countries

- NCD:

-

Not-Communicable Disease

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Assay

- RCT:

-

Randomised Controlled Trial

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic Condition

References

-

Earth Wellness Organization. Factsheet on overweight and obesity2018 Aug 2018. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

-

Lifshitz F, Rising R, Alemzadeh R. Obesity in children. Pediatr Endocrinol CRC Printing. 2006:25–60.

-

Dietz WH. Wellness consequences of obesity in youth: babyhood predictors of developed disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101(Supplement two):518–25.

-

Wang Y, Lim H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economical status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24(3):176–88.

-

Patton GC, Viner R. Pubertal transitions in health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2007;369(9567):1130–9.

-

Reilly JJ, Methven Due east, McDowell ZC, Hacking B, Alexander D, Stewart Fifty, et al. Health consequences of obesity. Curvation Dis Child. 2003;88(9):748–52.

-

Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, Ezeh Air conditioning, et al. Boyhood: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1630–xl.

-

Alberga Equally, Sigal RJ, Goldfield 1000, Prud'Homme D, Kenny GP. Overweight and obese teenagers: why is adolescence a disquisitional period? Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(4):261–73.

-

Blakemore SJ, Mills KL. Is adolescence a sensitive menstruum for sociocultural processing? Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;3(65):187–207.

-

Davis MM, Gance-Cleveland B, Hassink S, Johnson R, Paradis 1000, Resnicow Grand. Recommendations for prevention of babyhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Supplement 4):S229–S53.

-

Pearson N, Biddle SJ. Sedentary behavior and dietary intake in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):178–88.

-

Napier MA, Chocolate-brown BB, Werner CM, Gallimore J. Walking to school: community blueprint and kid and parent barriers. J Environ Psychol. 2011;31(ane):45–51.

-

Story Chiliad, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(3):S40–51.

-

Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J. School-based obesity prevention: a blueprint for taming the epidemic. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26(6):486–93.

-

Bleich SN, Vercammen KA, Zatz LY, Frelier JM, Ebbeling CB, Peeters A. Interventions to preclude global babyhood overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;half dozen(4):332–46.

-

Kanekar A, Sharma Chiliad. Meta-analysis of schoolhouse-based childhood obesity interventions in the UK and US. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2009;29(3):241–56.

-

Kobes A, Kretschmer T, Timmerman Thousand, Schreuder P. Interventions aimed at preventing and reducing overweight/obesity amongst children and adolescents: a meta-synthesis. Obes Rev. 2018;19(viii):1065–79.

-

Lavelle HV, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Systematic review and meta-assay of schoolhouse-based interventions to reduce body mass alphabetize. J Public Health. 2012;34(iii):360–9.

-

Lander N, Eather Northward, Morgan PJ, Salmon J, Barnett LM. Characteristics of teacher training in school-based physical educational activity interventions to improve primal movement skills and/or concrete activity: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2017;47(ane):135–61.

-

Wang D. Stewart ds. The implementation and effectiveness of school-based diet promotion programmes using a health-promoting schools approach: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(half-dozen):1082–100.

-

Dobbins M, Husson H, DeCorby M, LaRocca RL. School-based concrete activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to eighteen. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD007651.

-

Kriemler S, Meyer U, Martin E, van Sluijs EM, Andersen LB, Martin BW, et al. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(11):923–30.

-

Moores CJ, Bell LK, Miller J, Damarell RA, Matwiejczyk 50, Miller MD. A systematic review of customs-based interventions for the treatment of adolescents with overweight and obesity. Obes Rev. 2018;19(5):698–715.

-

Britain Section of Health. Guidance. Childhood obesity: a program for activeness 2017 Aug 2018. Available from: https://www.gov.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland/government/publications/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-activeness/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action.

-

Marks R. Health literacy: what is it and why should we care? In: Marks R, editor. Health literacy and school-based Instruction: Emerald Grouping Publishing; 2012.

-

Nutbeam D, Harris E, Wise West. Theory in a nutshell: a applied guide to wellness promotion theories. McGraw-Hill. 2010.

-

Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, Gidding SS, Hayman LL, Kumanyika S, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and handling. Circulation. 2005;111(fifteen):1999–2012.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

-

Khan KS, Ter Riet G, Glanville J, Sowden AJ, Kleijnen J. Undertaking systematic reviews of inquiry on effectiveness: CRD'southward guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 2001;No. 4 (2n).

-

Earth Health System. Wellness topics: Adolescent Health Available 2018. Bachelor from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/.

-

Wang Y, Chen HJ. Use of percentiles and z-scores in anthropometry. In: Handbook of anthropometry. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. p. 29–48.

-

The World Bank. World Bank Land and Lending Groups 2020 [August 2020]. Bachelor from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-globe-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

-

Green LW, Iverson DC. Schoolhouse health education. Annu Rev Public Health. 1982;3(i):321–38.

-

Amaro Southward, Viggiano A, Di Costanzo A, Madeo I, Viggiano A, Baccari ME, et al. Kaledo, a new educational board-game, gives nutritional rudiments and encourages good for you eating in children: a pilot cluster randomized trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2006;165(ix):630–5.

-

Bonsergent East, Agrinier N, Thilly N, Tessier S, Legrand K, Lecomte Eastward, et al. Overweight and obesity prevention for adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial in a school setting. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(1):30–nine.

-

Dewar DL, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC, Okely Advert, Collins CE, Batterham One thousand, et al. The nutrition and enjoyable activity for teen girls written report: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(3):313–7.

-

Ermetici F, Zelaschi RF, Briganti South, Dozio East, Gaeta Thou, Ambrogi F, et al. Association between a school-based intervention and adiposity outcomes in adolescents: the Italian "Eat" project. Obesity. 2016;24(3):687–95.

-

Fairclough SJ, Hackett AF, Davies IG, Gobbi R, Mackintosh KA, Warburton GL, et al. Promoting healthy weight in main schoolhouse children through concrete activity and nutrition education: a pragmatic evaluation of the Modify! Randomised intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:626.

-

Foster GD, Sherman S, Borradaile KE, Grundy KM, Vander Veur SS, Nachmani J, et al. A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(iv):e794–802.

-

Grydeland M, Bergh IH, Bjelland Thousand, Lien N, Andersen LF, Ommundsen Y, et al. Intervention effects on physical action: the HEIA report - a cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Deed. 2013;10:17.

-

Lazorick S, Fang Ten, Hardison GT, Crawford Y. Improved body mass index measures post-obit a middle school-based obesity intervention-the MATCH program. J Sch Health. 2015;85(10):680–seven.

-

Lubans DR, Smith JJ, Plotnikoff RC, Dally KA, Okely AD, Salmon J, et al. Assessing the sustained impact of a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent boys: the ATLAS cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:92.

-

Millar 50, Kremer P, de Silva-Sanigorski A, McCabe MP, Mavoa H, Moodie M, et al. Reduction in overweight and obesity from a three-year community-based intervention in Commonwealth of australia: the 'It's your movement!' project. Obes Rev. 2011;12(Suppl ii):xx–8.

-

Robbins LB, Pfeiffer KA, Maier KS, Lo YJ, Wesolek Ladrig SM. Pilot intervention to increase physical activity among sedentary urban middle school girls: a two-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental pattern. J Sch Nurs. 2012;28(4):302–15.

-

Viggiano A, Viggiano E, Di Costanzo A, Viggiano A, Andreozzi E, Romano Five, et al. Kaledo, a board game for nutrition teaching of children and adolescents at school: cluster randomized controlled trial of salubrious lifestyle promotion. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(ii):217–28.

-

Williamson DA, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Han H, Martin CK, Newton RL Jr, et al. Event of an environmental school-based obesity prevention program on changes in body fat and body weight: a randomized trial. Obesity. 2012;20(eight):1653–61.

-

Pfeiffer KA, Robbins LB, Ling J, Sharma DB, Dalimonte-Merckling DM, Voskuil VR, et al. Effects of the girls on the move randomized trial on adiposity and aerobic performance (secondary outcomes) in low-income adolescent girls. Pediatric Obesity. 2019;14(11):e12559.

-

Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Cowgill BO, Klein DJ, Hawes-Dawson J, Uyeda Chiliad, et al. Two-year BMI outcomes from a school-based intervention for diet and practise: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2016;137(v):e20152493.

-

Busch V, De Leeuw JR, Zuithoff NP, Van Yperen TA, Schrijvers AJ. A controlled health promoting schoolhouse study in the netherlands: furnishings after 1 and 2 years of intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2015;xvi(4):592–600.

-

Ezendam NP, Brug J, Oenema A. Evaluation of the web-based computer-tailored FATaintPHAT intervention to promote energy balance among adolescents: results from a school cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(3):248–55.

-

Graham DJ, Schneider M, Cooper DM. Television viewing: moderator or mediator of an boyish physical action intervention? Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(2):88–91.

-

Good for you Study Group. A school-based intervention for diabetes run a risk reduction. North Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):443–53.

-

Melnyk BM, Jacobson D, Kelly SA, Belyea MJ, Shaibi GQ, Small Fifty, et al. Twelve-month effects of the COPE healthy lifestyles TEEN programme on overweight and depressive symptoms in high school adolescents. J Sch Health. 2015;85(12):861–seventy.

-

Mihas C, Mariolis A, Manios Y, Naska A, Arapaki A, Mariolis-Sapsakos T, et al. Evaluation of a diet intervention in adolescents of an urban area in Greece: short- and long-term effects of the VYRONAS study. Public Wellness Nutr. 2010;thirteen(5):712–nine.

-

Neumark-Sztainer DR, Friend SE, Flattum CF, Hannan PJ, Story MT, Bauer KW, Feldman SB, Petrich CA. New moves—preventing weight-related bug in adolescent girls: a group-randomized study. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(v):421–32.

-

Peralta LR, Jones RA, Okely AD. Promoting healthy lifestyles amidst adolescent boys: the fitness improvement and lifestyle awareness plan RCT. Prev Med. 2009;48(vi):537–42.

-

Prins RG, Brug J, van Empelen P, Oenema A. Effectiveness of YouRAction, an intervention to promote adolescent physical action using personal and environmental feedback: a cluster RCT. PLoS Ane [Electronic Resource]. 2012;vii(3):e32682.

-

Rosenbaum M, Nonas C, Weil R, Horlick M, Fennoy I, Vargas I, et al. Schoolhouse-based intervention acutely improves insulin sensitivity and decreases inflammatory markers and body fatness in inferior high school students. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;92(2):504–8.

-

Singh AS, Chin APMJ, Brug J, van Mechelen W. Brusque-term furnishings of school-based weight gain prevention amidst adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(6):565–71.

-

Wadolowska L, Hamulka J, Kowalkowska J, Ulewicz N, Hoffmann Grand, Gornicka M, et al. Changes in sedentary and active lifestyle, diet quality and torso composition nine months later on an education program in smoothen students aged xi–12 years: report from the ABC of salubrious eating written report. Nutrients. 2019;11(ii):331.

-

Webber LS, Catellier DJ, Lytle LA, Murray DM, Pratt CA, Immature DR, et al. Promoting physical activity in eye schoolhouse girls: trial of activity for adolescent girls. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):173–84.

-

Wilksch SM, Paxton SJ, Byrne SM, Austin SB, McLean SA, Thompson KM, et al. Prevention across the Spectrum: a randomized controlled trial of iii programs to reduce risk factors for both eating disorders and obesity. Psychol Med. 2015;45(9):1811–23.

-

Young DR, Phillips JA, Yu T, Haythornthwaite JA. Effects of a life skills intervention for increasing physical activeness in adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(12):1255–61.

-

Fröberg A, Jonsson L, Berg C, Lindgren EC, Korp P, Lindwall Chiliad, et al. Effects of an empowerment-based health-promotion school intervention on concrete activity and sedentary time among adolescents in a multicultural area. Int J Environ Res Public Wellness. 2018;15(11):2542.

-

Benitez-Andrades JA, Arias North, Garcia-Ordas MT, Martinez-Martinez M, Garcia-Rodriguez I. Feasibility of social-network-based eHealth intervention on the improvement of salubrious habits among children. Sensors. 2020;twenty(5):04.

-

Robbins LB, Ling J, Clevenger Grand, Voskuil VR, Wasilevich E, Kerver JM, et al. A schoolhouse- and abode-based intervention to improve Adolescents' physical activity and healthy eating: a pilot written report. J Sch Nurs. 2020;36(2):121–34.

-

Robbins LB, Ling J, Wen F. Attending after-school physical activeness Club 2 days a week attenuated an increment in percentage body fat and a subtract in fitness amid adolescent girls at risk for obesity. Am J Wellness Promot. 2020;34(5):500–4.

-

Smith JJ, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC, Dally KA, Salmon J, Okely Advertizing, Finn TL, Lubans DR. Smart-phone obesity prevention trial for adolescent boys in depression-income communities: the ATLAS RCT. Pediatrics. 2014;134(iii):e723–31.

-

Schneider M, Dunton GF, Bassin South, Graham DJ, Eliakim A, Cooper DM. Touch of a schoolhouse-based physical action intervention on fitness and os in adolescent females. J Phys Human activity Wellness. 2007;4(ane):17–29.

-

Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Elliott MN, Klein DJ, Hawes-Dawson J, Uyeda Grand, et al. A randomized controlled trial of students for diet and practise: a community-based participatory research study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(3):415–22.

-

Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Alcaraz JE, Kolody B, Hovell MF, Nader P. R. Project SPARK. Effects of concrete education on adiposity in children. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;699:127–36.

-

Doak CM, Visscher TL, Renders CM, Seidell JC. The prevention of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a review of interventions and programmes. Obes Rev. 2006;vii(1):111–36.

-

Katz DL, O'Connell M, Njike VY, Yeh MC, Nawaz H. Strategies for the prevention and control of obesity in the school setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2008;32(12):1780.

-

Gonzalez-Suarez C, Worley A, Grimmer-Somers K, Dones V. School-based interventions on babyhood obesity: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):418–27.

-

Dietz WH, Gortmaker SL. Preventing obesity in children and adolescents. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22(i):337–53.

-

Rose T, Barker Chiliad, Jacob CM, Morrison L, Lawrence Westward, Strömmer Due south, et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical action behaviors of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61((6)):669–77.

-

Ajie WN, Chapman-Novakofski KM. Impact of figurer-mediated, obesity-related diet teaching interventions for adolescents: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(6):631–45.

-

Carbone ET, Zoellner JM. Diet and health literacy: A systematic review to inform nutrition research and exercise. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(2):254–65.

-

Tate DF. Awarding of innovative technologies in the prevention and treatment of overweight in children and adolescents. Handbook of childhood and adolescent obesity. Boston, MA.: Springer; 2008. p. 387–404.

-

Wood-Townsend Chiliad, Leat H, Bay J, Bagust L, Davey H, Lovelock D, et al. LifeLab Southampton: a program to engage adolescents with DOHaD concepts as a tool for increasing health literacy in teenagers–a pilot cluster-randomized command trial. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2018;9(5):475–fourscore.

-

Lazzer S, Boirie Y, Bitar A, Montaurier C, Vernet J, Meyer Thou, et al. Assessment of energy expenditure associated with physical activities in free-living obese and nonobese adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(three):471–ix.

-

Neumark-Sztainer D. Can we simultaneously piece of work toward the prevention of obesity and eating disorders in children and adolescents? Int J Swallow Disord. 2005;38(3):220–7.

-

Davies EL. "The monster of the calendar month": teachers' views well-nigh alcohol within personal, social, health, and economic education (PSHE) in schools. Drugs and Booze Today. 2016;16(4):279–88.

-

Milliken-Tull A, McDonnell R. Alcohol and drug teaching in schools 2017. Available from: http://mentor-adepis.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Mentor-ADEPIS-Mapping-Study-Oct-2017.pdf.

-

Morgan PJ, Young Dr., Smith JJ, Lubans DR. Targeted wellness behavior interventions promoting physical activeness: a conceptual model. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2016;44(2):71–80.

-

Mathews LB, Moodie MM, Simmons AM, Swinburn BA. The procedure evaluation of It's your move!, an Australian adolescent customs-based obesity prevention project. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):448.

-

Yager A, O'Dea JA. The role of teachers and other educators in the prevention of eating disorders and child obesity: what are the issues? Eat Disord. 2005;13:261–78.

-

Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Coller T. Perceptions of secondary school staff toward the implementation of school-based activities to prevent weight-related disorders: a needs assessment. Am J Health Promot. 1999;13(iii):153–vi.

-

Stang JS, Story M, Kalina B. School-based weight direction services: perceptions and practices of school nurses and administrators. Am J Health Promot. 1997;xi(three):183–v.

-

International Union for Health Promotion and Education. Promoting Health in Schools: From evidence to Activity 2010 [Available from: http://www.iuhpe.org/images/PUBLICATIONS/THEMATIC/HPS/Evidence-Action_ENG.pdf.

-

Reilly JJ, El-Hamdouchi A, Diouf A, Monyeki A, Somda SA. Determining the worldwide prevalence of obesity. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1773–4.

-

Nooyens Ac, Koppes LL, Visscher TL, Twisk JW, Kemper HC, Schuit AJ, et al. Adolescent skinfold thickness is a better predictor of loftier torso fatness in adults than is body mass alphabetize: the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(vi):1533–9.

-

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, DeCorby Chiliad, Bucknall TK, Kent B, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(one):33.

-

Klingberg Southward, Draper CE, Micklesfield LK, Benjamin-Neelon SE, van Sluijs EM. Childhood obesity prevention in Africa: a systematic review of intervention effectiveness and implementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;sixteen(7):1212.

-

Bann D, Johnson West, Li L, Kuh D, Hardy R. Socioeconomic inequalities in babyhood and adolescent torso-mass index, weight, and top from 1953 to 2015: an analysis of iv longitudinal, observational, British nascency accomplice studies. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(4):e194–203.

Acknowledgements

We also thank Liz Payne and Paula Sands for their assistance with the search strategy.

Funding

This paper presents independent enquiry funded by the National Institute for Health Enquiry (NIHR) under its Plan Grants for Applied Inquiry Programme (Reference Number RP-PG-0216-20004). CMJ is funded past the EU Horizon 2020 programme LifeCycle under grant agreement No. 733206. PHJ and MH are funded in function by the British Heart Foundation (PG/14/33/30827) and Wessex Heartbeat. KWT is supported by the National Constitute for Health Research, United Kingdom through the Southampton Biomedical Research Centre which also provides funds for work conducted by MH, HMI and CMJ. HMI and CMP are supported by the Great britain Medical Research Council and JB is partly funded by the UK Medical Enquiry Council. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and non necessarily those of the funding organizations listed above.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

JB, KWT, MH, HMI, PHJ and CMJ conceptualized the newspaper. PHJ, CMJ, JB, KWT, MB planned the methodology. PHJ, CMJ, MB investigated and screened the articles and conducted data extraction and quality assessment. HMI and CP conducted the meta-assay. PHJ and CMJ drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to the review and revision of the concluding newspaper. All authors have approved the manuscript and consented for submission.

Respective authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

N/A as systematic review of published literature.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publication of the manuscript, figures, tables and supplementary material.

Competing interests

KWT, MH and HI are directors of LifeLab, a non-turn a profit intervention at the Academy of Southampton and Southampton Academy Hospital, both registered charitable organizations. All other authors declare no conflicts of involvement. The proposal for this review was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42016053477).

Additional information

Publisher'due south Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Data

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits utilize, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, equally long every bit you give advisable credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and point if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article'south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the cloth. If material is not included in the article's Artistic Eatables licence and your intended apply is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted utilize, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/null/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this commodity

Jacob, C.M., Hardy-Johnson, P.L., Inskip, H.M. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions with wellness instruction to reduce body mass index in adolescents anile x to 19 years. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 18, 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01065-ix

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12966-020-01065-nine

Keywords

- Adolescent health

- Body mass index

- Obesity

- School

- Health education

- Physical activity

- Nutrition

- Nutrition

- Intervention

Source: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-020-01065-9

Post a Comment for "Peer Review Article on Health Education and Obesity in Schools"